Marine protected areas are designed to safeguard sea life and ecosystems by restricting or regulating certain human activities. They can be found along coastlines, in coastal waters, and on the high seas. However, these zones vary widely in their conservation goals and management strategies – and in the worst cases, the aims and measures exist only on paper, with little or no effective enforcement.

Who designates and oversees these protected areas depends on their location. Responsibility can lie with regional coastal authorities, national governments, or even the United Nations.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted in 1982 and came into force in 1994. It governs all forms of marine use and provides the legal framework for international ocean governance. While UNCLOS includes a dedicated section on the high seas, it only sets out general provisions for protection. A major milestone in safeguarding high seas biodiversity is the UN Convention “Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction” (BBNJ), which paves the way for establishing marine protected areas in international waters.

1. What are marine protected areas?

The coasts and oceans, along with their ecological services, resources and biotic communities, form the basis of human life on Earth. They provide us with oxygen and food, protect our coasts from erosion and store climate-damaging carbon dioxide. They also offer millions of people work, recreation and inspiration, as well as providing a sense of cultural identity. However, the services provided by marine ecosystems are increasingly at risk due to human exploitation and the effects of climate change. Too much fish is being caught on an industrial scale; species-rich coastal and marine habitats, such as mangroves, reefs and seagrass beds, are being destroyed; and plastic waste, sewage and pollutants are ending up in the ocean. Greenhouse gas emissions are also fuelling climate change. This, in turn, increases heat stress for sea animals and plants, causes the ocean to become increasingly acidic, and results in a drop in the oxygen content of seawater. The risk of extinction for marine species therefore increases with every tenth of a degree of additional global warming.(1)

Protected areas regulate or prohibit certain human activities to protect marine life and habitats. They are seen as an important instrument in the fight against the over-exploitation of the sea and associated species extinction.

When a marine area can truly be called a protected area is often difficult to determine. Countries designate such zones based on varying regulations and sometimes use different terms to describe them. As a result, protected areas come in many shapes and sizes, with differing standards and conservation goals.

In so-called “no-take zones”, for example, all extraction of resources – including fish, oil, gas, sand, and gravel – is strictly prohibited.

The core objective: Conserve species, habitats and their functions

Marine protected areas are established by a range of institutions and often pursue differing objectives. Their designation is therefore always a political decision and rarely without controversy. There are also various ways of classifying a marine area as protected. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), for example, defines a protected area as

“a clearly defined geographical area that is recognised, designated and managed through legal or other effective means, with the aim of conserving nature, its ecosystem services, and cultural values in the long term”.

According to the IUCN, protected areas do not include areas where harmful-scale fishing, mining or other extractive activities are carried out. The same applies to marine regions in which only one species or one harmful fishing technique is protected or prohibited, respectively. In such areas, the core objective of a marine protected area — the long-term protection and conservation of marine organisms and their habitats — cannot be guaranteed.

According to the IUCN, marine protected areas must meet six fundamental requirements. They should:

- Primarily aim to conserve nature,

- Pursue clear conservation objectives that reflect the goals of preserving the natural environment,

- Be of a size, location and design that effectively allows for the protection and maintenance of habitats and biodiversity,

- Have clearly defined and agreed boundaries,

- Be supported by a management plan capable of delivering the stated conservation goals, and

- Be established by individuals or institutions with sufficient resources and capacity to implement that management plan effectively.

Seven categories of protected areas

IUCN experts classify marine protected areas into one of seven categories, depending on the conservation objectives and the associated management plan. These range from fully protected areas, where extraction is completely banned, to areas that continue to be extensively used by humans. The greater the level of protection, the more restrictions are placed on the use and exploitation of the relevant ecosystems.

| Category | Name of the protected area | Protection goals and measures |

|---|---|---|

| Ia | Strict Nature Reserve | Biological diversity is strictly protected, including geological and geomorphological features where applicable. Human visits, use and impact are controlled and limited. |

| Ib | Wilderness area (large unaltered or slightly altered area without permanent or significant human settlement, which is intended to preserve its natural character and influence) | A protected area that is managed primarily for research purposes or to preserve large, pristine wilderness areas. |

| II | National Park (a large natural or near-natural area set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the characteristic species and ecosystems of the area) | Protected area managed primarily for the protection of ecosystems and for recreational purposes. |

| III | Natural monument | Protected area managed primarily to protect a special natural feature (submarine mountain, underwater cave, etc.). |

| IV | Habitat or species management area with active management to protect particular species or habitats | Protected area managed through targeted interventions. |

| V | Protected landscape/protected marine area: an area where the interaction between humans and nature over time has created a special character of significant ecological, biological, cultural and landscape value | An area whose management is primarily focused on protecting a landscape or marine area and which serves recreational purposes. |

| VI | Resource protection area or cultural landscape with management | Protected areas with sustainable use of natural ecosystems and habitats. |

2. How much marine area is protected and where?

The number of marine protected areas has risen sharply in recent years – all around the world. However, because definitions and standards for protected areas vary, there is not just one single set of statistics, but several. Whenever figures are quoted, it is therefore essential to consider who compiled the data and which criteria were used in selecting and categorising the areas.

According to the Marine Protection Atlas, only 3% of the global ocean area was considered comprehensively protected from fishing in February 2025. At that time, the Atlas listed 221 strictly protected marine areas, known as no-take zones, where fishing and other destructive activities were prohibited. The two largest of these were the Ross Sea Protection Area in the Southern Ocean and the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument off the northwest coast of Hawaii.

Many small protected areas with fishing bans were found in tropical and subtropical waters, primarily in areas of high biodiversity. According to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), there were also more than 16,000 protected areas around the globe where fishing and other forms of resource extraction were permitted to some extent. These 'less protected' areas included the marine protected areas in the German North Sea and Baltic Sea.

In February 2025, the WDPA reported that a total of 8.34 percent of the world's oceans were protected to some extent.

For this reason, Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) of the United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda stipulates that at least ten percent of the world's marine areas should be protected by 2020. This goal was expanded in 2022.

The 30x30 protection target

By 2030, 30 per cent of the ocean’s surface is to be designated as protected areas, with one third of that – amounting to 10 per cent of the total – under full no-take protection. This target was agreed by the member states of the international Convention on Biological Diversity as part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

The European Union has enshrined this target in its Biodiversity Strategy. The legal framework relevant for its implementation includes the EU Birds Directive, the Habitats Directive, and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive.

3. Marine protected areas on the high seas

Most marine protected areas are located in national waters because the respective coastal state can usually decide independently on the protection status and goals. In contrast, declaring protected areas in international waters (the high seas), which are far from any national coastline, requires the consent of many states and stakeholders, making it more difficult. Nevertheless, there are already several protected areas on the high seas, including those south of the South Orkney Islands and in the Ross Sea (Antarctica, CCAMLR region), as well as in the north-eastern part of the Atlantic Ocean (OSPAR region). At 1.55 million square kilometres, the Ross Sea Protected Area is the world's largest marine protected area. The OSPAR protected areas cover around 460,000 square kilometres, an area larger than Germany and Austria combined.

The establishment of marine protected areas on the high seas is often hindered by a lack of rules and legal foundations. The new UN High Seas Protection Agreement aims to address this issue.

Another major challenge is monitoring marine protected areas in international waters, as these zones are often located far out on the high seas. The success of such protection efforts depends on whether all relevant parties can agree on who is responsible for overseeing implementation, when and how monitoring takes place, and which scientific methods are used to document whether and to what extent the protected status is benefiting the affected ecosystems.

Adding to the difficulty is the fact that marine protected areas on the high seas are sometimes established with time limits. The duration of protection depends on the international agreement under which the area was designated. For example, the Ross Sea protected area under CCAMLR has a term of 35 years. An extension is likely to be considered only if scientific evidence clearly shows that the Ross Sea’s ecosystems have benefited from the protected status. This is another reason why clear rules for monitoring and evaluating these protected areas are so crucial.

4. Do protected areas safeguard marine life?

The success of a protected area can only be measured by its conservation goals, which often vary. It is easier to identify the environmental hazards against which marine protected areas offer little or no protection – primarily because ocean and air currents carry heat, water and everything in them to the farthest corners of the ocean. Marine protected areas therefore cannot protect their inhabitants from rising water temperatures, oxygen depletion, increasing acidification, overfertilisation, pollution, disease, rising sea levels or invasive species.

However, some marine regions will be affected by climate change and environmental hazards later than others. Protected areas in these regions provide refuge. Furthermore, researchers hypothesise that communities and species not exposed to human-driven extraction or destruction are better equipped to adapt to the consequences of climate change than those heavily impacted or destroyed.

The effectiveness of protected areas also depends on the extent to which the proposed conservation measures are actually implemented. When a marine protected area fails to meet its conservation goals because none of the planned restrictions or actions have been put into practice, it is referred to as a "paper park" – a protected area that exists in name only. Experts currently estimate that more than 70 per cent of existing marine protected areas are failing to achieve some or all of their conservation goals.

For this reason, many argue that effective marine conservation is not just a matter of how many areas are protected or how large they are (quantity), but how well these areas actually fulfil their conservation role and how rigorously the protection measures are enforced (quality). Another important factor is whether protected areas are designed to conserve local habitats – and with them, sedentary or territorial species such as those found in coral reefs, seagrass meadows, seamounts or kelp forests – or whether the aim is to protect migratory or mobile species such as fish, sharks or whales. Depending on the conservation goal, the effectiveness of a protected area can vary significantly.

Before-after, inside-outside: how researchers measure the protective effect

To evaluate the benefits of a marine protected area, scientists must first record the initial state of the ecosystem. They can then investigate how biological parameters change in the short and long term as a result of protection measures. To achieve this, they primarily record the distribution and population density of selected species, their biomass, age and size structure, and the species richness of ecosystems within the planning area.

When evaluating success, researchers also refer to data from comparable unprotected marine areas further afield in order to identify specific protective effects. However, in order to avoid misleading differences in the results, the environmental conditions (e.g. depth, currents, sediment composition) in the unprotected areas used for comparison must be as identical as possible to those in the protected areas. A constant challenge when measuring success is excluding other influencing factors, such as climate change or increasing marine pollution. These factors can negate possible protective effects or distort the results of the before-and-after comparison.

A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of no-take marine protected areas has shown that key biological indicators generally improve - though often only within the boundaries of the protected zones, and not equally across all species studied. There are also significant differences in outcomes from one protected area to another, raising the question of why some are more successful at conserving marine life than others.

It is widely accepted that the larger a protected area, the longer it has been in place, and the more strictly all bans are enforced - particularly on fishing, dredging and other resource extraction - the greater the recovery of marine life. However, only a few studies to date have examined changes across entire ecosystems, going beyond the monitoring of individual key species, such as commercially valuable fish. As a result, we still lack a clear understanding of how protection affects the full range of ecosystem functions within a marine reserve, or what knock-on effects may occur within the food web. For instance, how does an ecosystem change when a predator species is no longer fished and begins to return in greater numbers?

This is where marine science has a vital role to play. New research approaches are needed to gain deeper insight into the dynamics of marine ecosystems and biodiversity networks, and to build a more comprehensive understanding of how they function. Both are essential for better evaluating the effectiveness of existing marine protected areas and for planning new ones more effectively.

How can fish stocks be protected?

More than a quarter of the world’s monitored fish stocks are overfished. As a result, experts are urgently searching for ways to restore vulnerable populations. Some specialists advocate for a comprehensive network of no-take marine protected areas, where all fishing is strictly prohibited. Research shows that within such zones, fish populations increase and seabed communities begin to recover - particularly mussels, corals, sponges, and other sedentary organisms that were previously disturbed by bottom trawling.

Other experts, however, consider fishing bans to be ineffective. They instead favour comprehensive fishing regulations, including strict catch quotas and limited fishing seasons, as well as a ban on destructive or bycatch-intensive techniques in sensitive areas. They argue that a fishing ban would primarily lead to affected fishermen moving to neighbouring regions of the protected area, thereby increasing the risk to the marine environment there. Moreover, fishing would rarely be reduced.

So far, marine research has provided arguments for both sides of this controversy. For example, model calculations suggest that a protected area can increase fish abundance and catch outside its boundaries, but only if fish stocks in the region are heavily overfished and fishing pressure outside the protected area is high. In regions with little or no fishing regulation, a network of no-fishing zones can help communities in the water column and on the seabed to recover.

However, it is unclear whether the fish population of a marine area increases when only parts of it are protected, or under what circumstances this occurs. It is also unclear whether undisturbed fish spawning within a protected area would lead to an increase in fish abundance outside the area in the long term.

Migratory marine species: Protection at the right time

Even more challenging than preserving stationary marine habitats such as reefs, sandbanks, or seagrass meadows is the protection of migratory marine species. These include whales, seals, sharks, rays, seabirds, and sea turtles, as well as many popular food fish such as tunas. These animals often travel thousands of kilometres on their migrations, frequently moving outside designated protected areas.

Nevertheless, research shows that even small and medium-sized marine protected areas can contribute to protecting them. This is particularly true when the protected areas are located in regions where animals spend important life stages, such as reproduction, egg laying, or the birth and rearing of their young. In the case of fish, regions where eggs and larvae are laid, or where young migrate, must also be protected.

The effectiveness of protective measures also depends on how well countries whose coastal waters are crossed by migrating animals cooperate with each other. Ideally, coastal states would form a network of marine protected areas with corridors through which the animals could migrate undisturbed.

However, even under the best conditions, a protected area can never accommodate all species simultaneously because their movement patterns differ too greatly from one another. Opponents of protected areas with fishing bans argue that fish stocks would be better protected if strict fishing regulations were enforced universally at the oceans, rather than just in geographically limited protected areas. They argue that such sustainable fishing would reduce pressure on the marine environment and secure the long-term supply of fish and seafood.

5. Planning and implementing marine protected areas

Conflicts of interest are common in every marine region, particularly in intensively used coastal waters. For marine protected areas to be successfully implemented, the various demands on the ocean must be considered from the outset, and the affected population groups must be involved in the planning process.

Under what circumstances do marine protected areas fuel conflicts?

A marine protected area always comes with restrictions for people. Fishing is often allowed only to a limited extent, only at certain times, or not at all. In some cases, boating, anchoring and diving are also prohibited, excluding the area from tourism. For those who depend on the ocean’s resources for their livelihoods - sometimes over generations - such measures can mean losing access to areas they have long relied upon.

As a result, conflicts over use arise, where the collective interest in marine conservation clashes with individual needs to secure an income. In many cases, entire families depend on exploiting the ocean for their survival. Declaring a protected area, therefore, is not only an ecological and economic decision, it often carries significant social consequences. Each marine reserve raises the following question: Do the environmental and biodiversity benefits outweigh the disadvantages for local communities, and how can those negative impacts be reduced?

A range of approaches has proven effective in practice. When planning smaller marine protected areas near the coast, it can be highly beneficial for local communities to work alongside experts in deciding which areas should be protected and to what extent, in order to achieve the best possible outcomes for both the marine environment and the people who depend on it.

Local fishing families often have the most in-depth knowledge of the area's resources and the traditional ways in which they have been managed and used. Moreover, when people are directly involved in setting the rules and understand the goals behind them, they are far more likely to support and uphold them.

However, when it comes to larger protected areas on the high seas, it is beneficial for a government to take the lead and coordinate cross-border cooperation with neighbouring countries. It must also ensure that all affected population groups are involved in the planning and decision-making processes, and that they actually have a say. Otherwise, people will hardly adhere to the new rules and will not contribute to their implementation.

Scientists have identified several success factors for planning and implementing marine protected areas. These include:

- involving all stakeholders affected by the protected area in the planning process from the outset

- conducting all discussions and decisions in a transparent manner;

- showing the local population alternative sources of income and raw materials;

- enabling affected people to develop alternative sources of income through further education, training, and technical and financial assistance;

- adapt the planning process and the conservation concept to local conditions.

Adhering to these guidelines will prevent new marine protected areas from exacerbating social injustices and placing an even greater burden on disadvantaged population groups.

Monitoring the impact of protected areas requires new scientific methods to analyse the interactions between the marine environment, its users and other social stakeholders. Some initial approaches already exist. One such approach is socio-ecological network analysis. This method is primarily used by interdisciplinary experts to predict and assess the consequences of economic restrictions on various user groups and the marine environment more accurately. New remote sensing technologies are also proving highly valuable, making it easier to detect illegal fishing activities within protected areas or destructive practices such as the overexploitation of mangrove forests.

The future success of marine protected areas will also depend on their ability to move with the species they are intended to protect. Due to climate change, marine life is already undergoing significant shifts in distribution. To ensure the continued protection of particularly vulnerable species, protected areas must be designed with flexibility in mind, monitored closely and adjusted in line with the pace of these migrations. Achieving this will once again require strong cooperation between governments, decision-makers and those directly affected.

6. Marine protected areas in the German North Sea and Baltic Sea

Almost 45 per cent of the German North and Baltic Seas are designated as protected areas. These areas serve to protect marine mammals such as the harbour porpoise and grey seal. They are also intended to provide safe havens for species such as sturgeon, twaite shad and numerous seabirds, as well as helping to preserve important habitats such as reefs and sandbanks. However, the necessary protective measures have not yet been fully implemented.

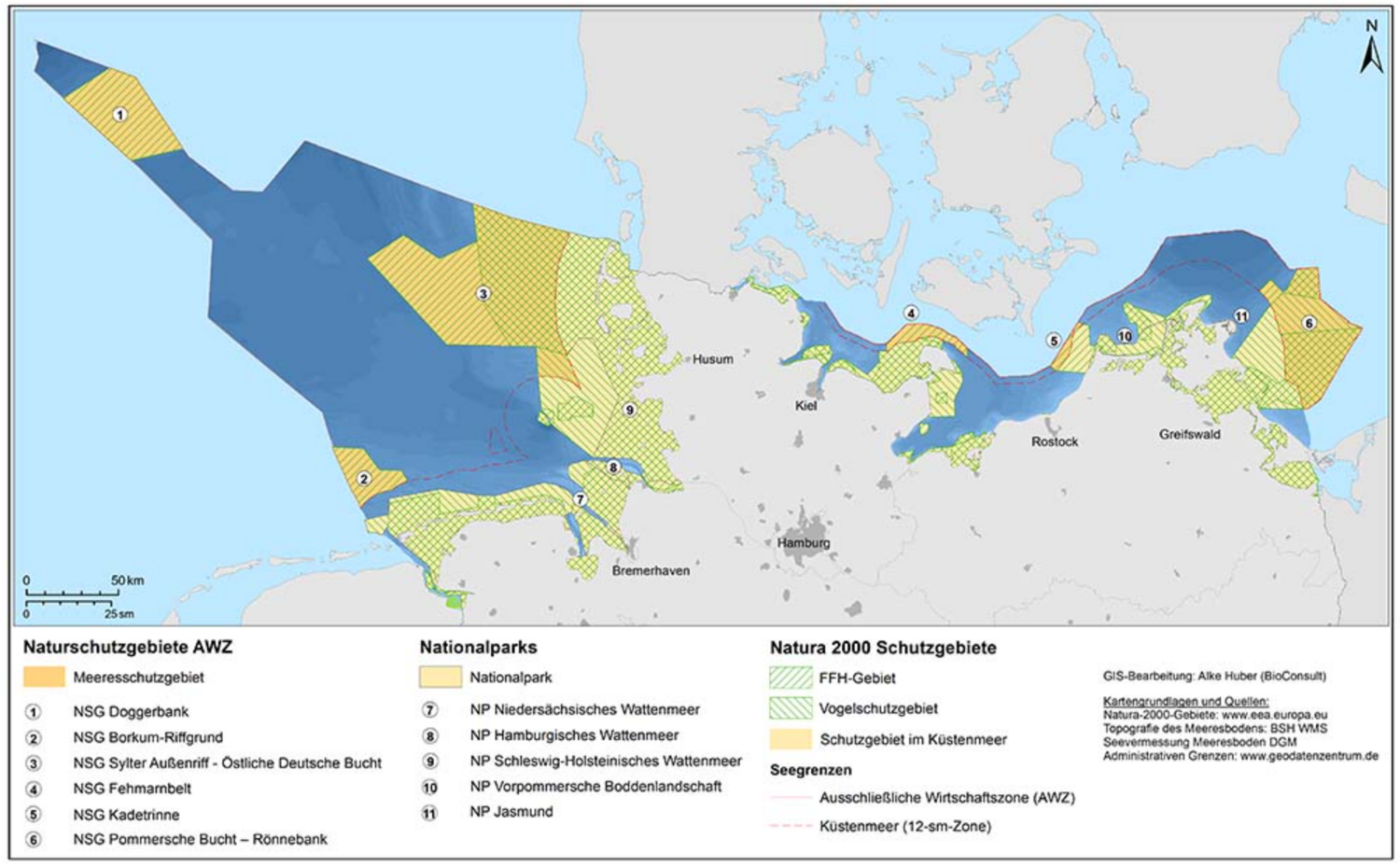

The German marine protected areas include three national parks in the Wadden Sea in the North Sea, two national parks in the coastal waters of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and six nature reserves in the German Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which extends 12 to 200 nautical miles from the coast. (See map.) There are also other Natura 2000 protected areas in coastal waters. These marine areas are part of an EU-wide network of protected areas.

Responsibility of the federal government and coastal states

The coastal protected areas are managed by the states of Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony, Hamburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, which have coastlines. The federal government, represented by the Federal Ministry for the Environment and the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN), is responsible for nature conservation areas within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). BfN experts have drawn up the corresponding management plans. The protection zones in the EEZ are also set out in the marine spatial plan. This document outlines the permitted uses of the marine areas within the German EEZ.

All assessments of the state of marine ecosystems - and any changes within the marine protected areas of the North Sea and Baltic Sea - are carried out according to the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive. This directive provides a common framework for action and assessment. In adopting it in 2008, the European Union committed to aligning the protection and use of its marine waters. The goal was to significantly improve the marine environment by 2020 and ensure the long-term health of marine ecosystems. However, the action plan linked to the directive has progressed far more slowly than expected in recent years. The 'good environmental status' demanded by the directive remains a distant target.

Environmental status of the North Sea and Baltic Sea

Every six years, experts assess the environmental status of Germany's marine areas. The 2024 comprehensive report shows that the German North Sea and Baltic Sea are in poor condition. This summary focuses on the results of the status reports for Germany's coastal and marine waters.

Mandates of marine nature conservation in Germany

Marine nature conservation comprises various protection mandates aimed at specific assets. As well as species protection, key elements include protecting areas and conserving, restoring or developing biotopes and biotope networks. Examples include salt marshes and mudflats in coastal areas, seagrass beds, reefs, sandbanks and mudflats with boring-bottom megafauna, as well as species-rich gravel, coarse sand and shingle beds in marine and coastal areas.

Most of Germany’s marine protected areas fall under the Natura 2000 conservation framework. This means that certain activities are generally prohibited in order to safeguard the designated species and habitats in line with specific conservation goals. Banned activities include the construction of installations and infrastructure, fishing with gillnets or with bottom towed gear, the establishment of aquaculture operations, and the dumping of dredged material.

Other uses, however, are permitted in most protected zones. Experts have identified 17 different types of use within the marine protected areas of Germany’s Exclusive Economic Zone in the Baltic Sea alone. These include recreational and commercial shipping, fishing, the laying of cables and pipelines, as well as military exercises conducted on, under or above the water. In some areas, also bottom trawling is still allowed.

The Wadden Sea World Heritage Site

The Wadden Sea is a unique, species-rich coastal landscape. In 2009, it was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The countries of Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands are working together to protect this landscape, characterised by high and low tides, for present and future generations.

- Adams, V.A., et al. (2023): Multiple-use protected areas are critical to equitable and effective conservation. One Earth 6(9):1173-1189, DOI:10.1016/j.oneear.2023.08.011

- Conners, M. G., et al. (2022): Mismatches in scale between highly mobile marine megafauna and marine protected areas. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 897104, DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2022.897104

- Dahood and G.M. Watters (2018): Candidate baseline data for ecosystem indicators in the Ross Sea region, WS-SM-18/02 06 June 2018, CCAMLR

- Bundesamt für Naturschutz, bfn.de

- Bundesamt für Naturschutz (Hrsg.) (2020): Die Meeresschutzgebiete in der deutschen AWZ der Ostsee – Beschreibung und Zustandsbewertung. Erstellt von Bildstein, T., Schuchardt, B., Bleich, S., Bennecke, S., Schückel, S., Huber, A., Dierschke, V., Koschinski, S., Darr, A. BfN-Skripten 553,. 497 S.

- Day, J., Dudley, N., Hockings, M., Holmes, G., Laffoley, D., Stolton, S., Wells, S. and Wenzel, L. (eds.) (2019). Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas. Second edition. Gland. Switzerland: IUCN.

- Di Cintio, A., et al. (2023): Avoiding “Paper Parks”. A Global Literature Review on Socioeconomic Factors Underpinning the Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. Sustainability 2023,15, 4464. DOI: 10.3390/su15054464

- Earth Negotiation Bulletin, Vol. 25 No. 252 Online at: bit.ly/BBNJ_IGC_5-3 Friday, 23 June 2023

- Edgar, G.J., et al. (2014). Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features, Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature13022

- Estradivari, A. et al. (2022): Marine conservation beyond MPAs: Towards the recognition of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) in Indonesia. Marine Policy, 137. p. 104939. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104939.

- FAO (2022): The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation. Rome, FAO. DOI: 10.4060/cc0461en

- Hilborn, R. (2018): Are MPAs effective?, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 75, Issue 3, May-June 2018, Pages 1160–1162, DOI: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx068

- Hilborn, R., Akselrud, C. A., Peterson, H. & Whitehouse, G. A. (2021): The trade-off between biodiversity and sustainable fish harvest with area-based management, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 78, Issue 6, September 2021, Pages 2271–2279, DOI: 10.1093/icesjms/fsaa139

- Hilborn, R., Kaiser, M.J. (2022): A path forward for analysing the impacts of marine protected areas. Nature 607, E1–E2 (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04775-1

- IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35-115, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

- Janssen et al. (2022): Integration mariner Naturschutzbelange in die zukünftige deutsche Meeresraumordnung. BfN, DOI: 10.19217/skr601

- Kriegl, M., Elías Ilosvay, X. E., von Dorrien, C. & Oesterwind, D. (2021): Marine Protected Areas: At the Crossroads of Nature Conservation and Fisheries Management. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8, 676264. DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2021.676264

- Marine Protection Atlas, mpatlas.org

- Wadden Sea Quality Status Report, https://qsr.waddensea-worldheritage.org/