Life in the ocean depends on carbon dioxide (CO₂). Marine plants such as microalgae, seagrasses and kelp use CO₂ for photosynthesis. In this process, they convert carbon dioxide into sugar (glucose) and oxygen with the help of sunlight. The sugar serves as both an energy source and a building material, enabling them to grow and reproduce. At the same time, algae, seagrasses and kelp form the basis of the food web for many other marine animals – for example zooplankton, which in turn is eaten by larger predators such as fish, baleen whales and penguins.

The acidity of the sea

Seas and oceans absorb CO₂ at their surface. As soon as this greenhouse gas dissolves in seawater, it causes a chemical change in the surface water. Unlike, for example, oxygen, carbon dioxide does not simply dissolve in seawater. A proportion of the gas reacts with water molecules to form carbonic acid. The molecules of this acid then, with very few exceptions, immediately split into bicarbonate and a hydrogen cation, also known as a proton.

The released protons increase the acidity of the water. If the ocean absorbs large additional amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, it therefore runs the risk of becoming more acidic, which worsens the living conditions for many marine organisms.

However, how many protons are actually released during the dissociation of carbonic acid depends on the acid-buffering capacity of seawater. This capacity is determined by mineral components in the water, which originate mainly on land. Over millions of years, they have been released from weathered rock and then transported into the sea by rainwater, streams and rivers.

If the proportion of these introduced minerals is high, seawater has a high buffering capacity. Scientists refer to this as high alkalinity. In this case, many of the protons are not released at all but are immediately bound by the minerals during the dissociation of carbonic acid. If, however, the water contains only small amounts of mineral components, its buffering capacity is limited. The number of free protons increases and the sea becomes increasingly acidic.

The lower the pH value of seawater, the greater its acidification

The concentration of hydrogen cations, or protons, in a solution is measured using what is known as the pH value. It indicates how acidic or alkaline a liquid is. The pH scale ranges from 0 (very acidic) to 14 (very alkaline). This means that the more hydrogen cations are present in a solution, the lower the pH value.

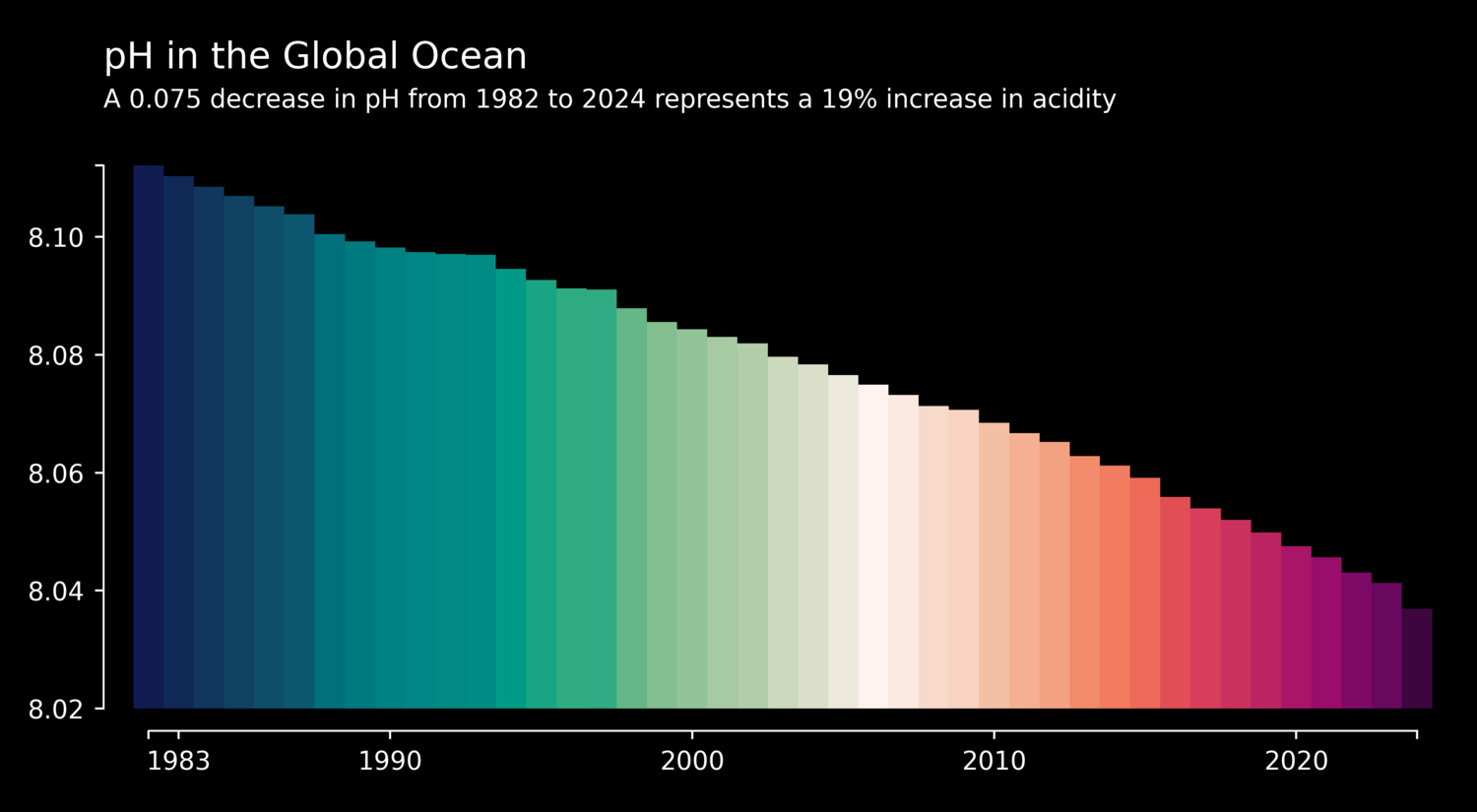

Since the beginning of industrialisation more than 250 years ago, the average pH value of the ocean surface has fallen from 8.2 to 8.1. This seemingly small change on the logarithmic pH scale corresponds to a real increase in acidity of 26 per cent – a change unlike anything the world’s oceans and their inhabitants have experienced over the past several million years.

The increasing acidification of the oceans affects various biological processes and thus the lives of many marine organisms. As the availability of carbonates in seawater decreases, it becomes more difficult in particular for calcifying organisms such as corals, mussels, pteropods and foraminifera to build their shells or skeletons. These structures become thinner and more fragile. It is known that echinoderms such as sea urchins and starfish grow less and die earlier as acidification increases. Fish are especially vulnerable as embryos within the egg and as larvae, since in these early stages of development they do not yet possess a functioning acid–base regulation system.

It is also still unclear to what extent different marine organisms are able to adapt to ocean acidification. Single-celled algae and small zooplankton with short reproductive cycles appear to be better equipped than larger organisms with long reproductive cycles.

CO₂ is therefore, on the one hand, essential for marine organisms, but on the other hand an imbalance caused by too much CO₂ in the water can severely disrupt the marine ecosystem.

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Instituion (WHOI) (o.D.). Know Your Ocean. Ocean Topics - Ocean Acidification. www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-chemistry/ocean-acidification/

![[Translate to English:] the graphic shows the chemical processes involved in the carbon dioxide uptake by the ocean](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/7/csm_co2uptake_cdrmare-scaled_en_cc043069c5.jpg)