The ocean plays a key role in the Earth's climate system. In summer, it stores solar energy in the form of heat and releases it back into the atmosphere in winter. At the same time, the large surface ocean currents distribute heat across the globe. The ocean absorb most of this heat from the atmosphere in the tropics and then transport it north or south.

The powerful Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, for example, which includes the Gulf Stream, transports tropical heat far into the North Atlantic. In temperate or high latitudes, the water masses release most of this heat. As a result, air temperatures over the North Atlantic rise, making the climate in Europe milder than it would be without the heat input from the Atlantic Ocean.

The ocean constantly distributes heat, regardless of whether the Earth is warming or not. In times of climate change, however, its capacity to absorb and store heat and gases from the atmosphere takes on a new and crucial importance.

When the concentration of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the Earth’s atmosphere rises and the air warms as a result, the ocean absorbs both a significant share of the excess heat and part of the CO₂ emitted by human activity. In doing so, it helps slow global warming to some extent and is an indispensable climate buffer.

The great ocean currents then transport the absorbed heat and the carbon dioxide dissolved in surface waters, storing both at increasing depths.

However, the climate services provided by the ocean—essential for our survival—come at a cost: when CO₂ from the atmosphere dissolves in the ocean’s surface waters, its chemistry changes. Ocean acidification intensifies, increasing, among other things, the energy required by mussels, corals, and other calcifying organisms to build and maintain their shells, skeletons, and carapaces.

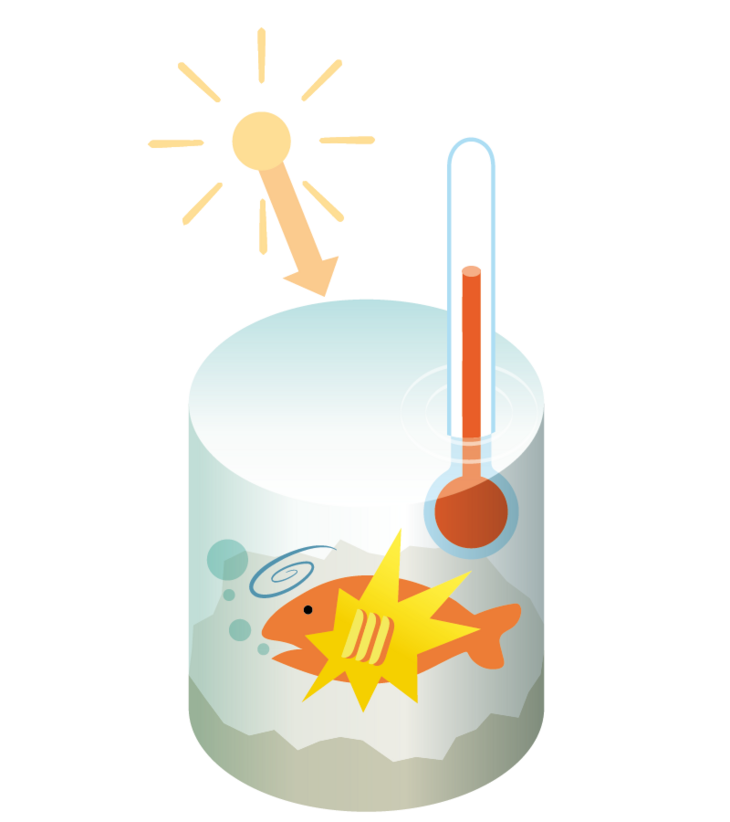

The constant absorption of heat leads to ocean warming, which affects water masses at ever greater depths and causes many organisms to suffer from heat stress. This stress can become extreme—and even fatal—during so-called marine heatwaves, defined as periods when water temperatures remain significantly above normal for at least five consecutive days.

Heat also alters the chemical and physical properties of seawater. For instance, it reduces the ocean’s capacity to store oxygen. As a result, a large share of marine life experiences respiratory stress and faces significantly lower chances of long-term survival. In addition, warmer water expands. The resulting sea level rise poses the risk of low-lying islands and coastal regions being flooded by the sea.

Another consequence is that warming oceans release more heat and moisture into the atmosphere. Where this occurs, storms and heavy rainfall systems develop—whose intensity and destructive power are demonstrably increasing as a result of climate change.

To mitigate the severe impacts of climate change on the ocean, humanity must halt the emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. At the same time, we must reduce all other human-induced stressors affecting marine life. These include, for example, the overfishing of key fish stocks, the pollution of the ocean with waste, plastics, and numerous other contaminants, the extraction of oil, sand, and gravel, as well as the destruction of vital coastal and marine habitats through the construction of cities, ports, shipping channels, and other infrastructure.

The fewer stressors marine life is exposed to, the greater its chances of adapting to the consequences of climate change.

![[Translate to English:] Cumulonimbus Wolke über Meereshorizont vom Forschungsschiff Sonne aus fotografiert.](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/d/csm_2_Kategorie_Klimawandel_Ralf_Prien_IOW_c7df98bc2b.jpg)