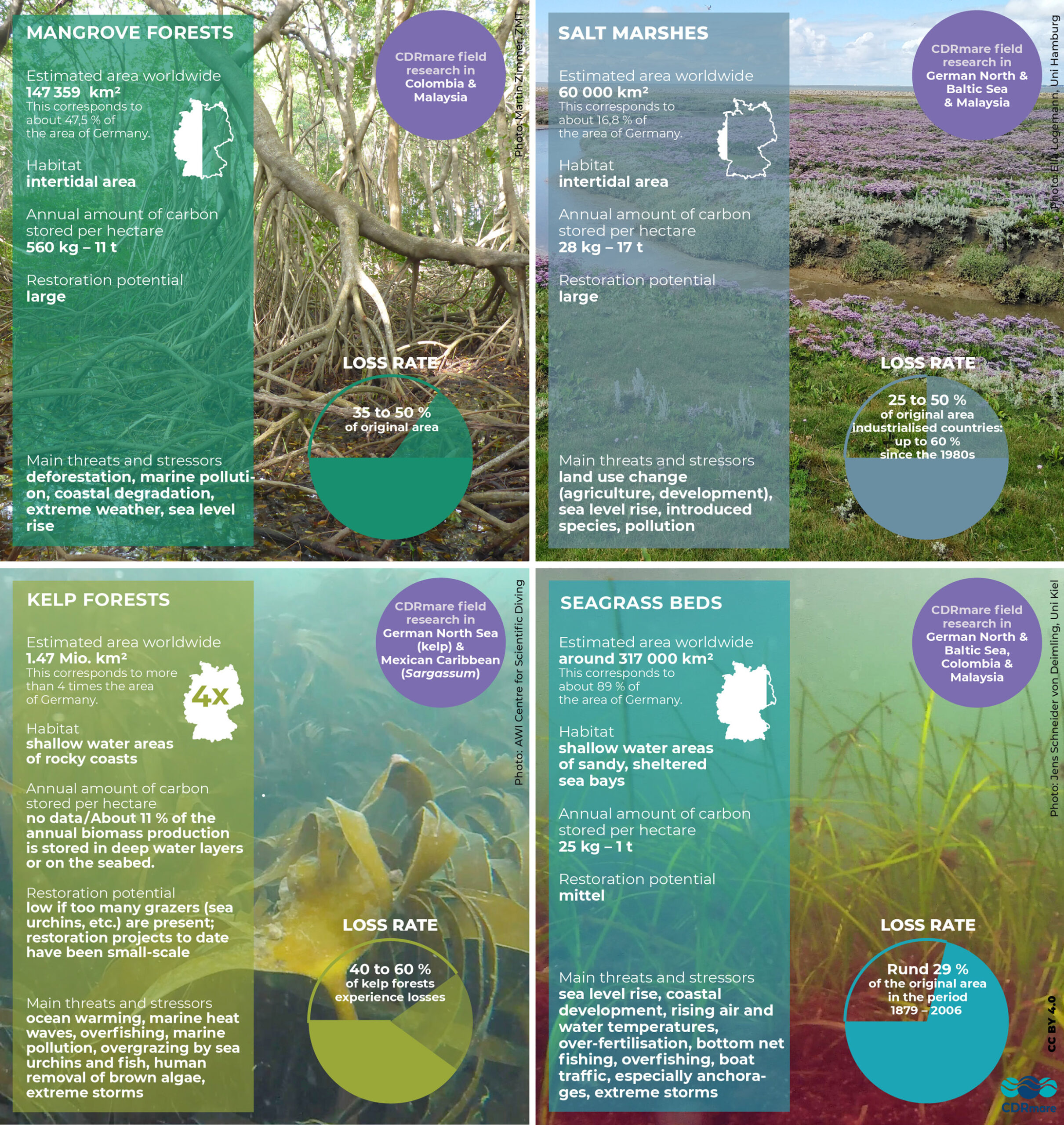

1. High losses of coastal ecosystems

In order to strengthen marine life, we must first and foremost protect and preserve the remaining intact habitats in our oceans. This includes deep-sea floor communities, ecosystems in successfully implemented protected areas worldwide, and communities in those parts of the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans that remain difficult for humans to access.

Humans have left clear traces in many other marine regions, especially in the coastal waters of continents. More than a third of monitored fish stocks are overfished, 85 per cent of mussel beds have disappeared, and 20 to 50 per cent of tropical coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangrove forests and kelp forests have been severely damaged or even wiped out. The adjacent graphic summarises the current state of affairs, the main threats and the rates of loss for four coastal ecosystems.

Tropical coral reefs, which are particularly affected, are not shown in the graph. In the catchment area of Australia's Great Barrier Reef, for instance, almost 10 per cent of the entire coastline (2,300 km) had been replaced by stone dams, marinas, jetties, and other urban infrastructure by 2015. Numerous sections of the coral reef were lost during this construction work. Coastal development also increased the fragmentation of this sensitive tropical ecosystem.

2. Key strategy for ending species decline

For marine biodiversity to recover, these key habitats must be restored. Ecological restoration is understood by experts to be the process that creates conditions enabling damaged, degraded or destroyed ecosystems to recover and adapt to local and global changes. The main goal is to ensure the survival and development of species within the ecosystem.

Although people in some coastal regions have cultivated shellfish beds, planted seagrass and bred large algae for thousands of years to ensure a sufficient food supply and improve water quality, research into the restoration of marine habitats is still in its infancy.

Consequently, experts are often unable to compare projects or identify clear success factors. For instance, it typically takes several years to prove the success of a reintroduction project and compare it with the results of other measures.

3. Guiding principles for successful recovery

Experts have derived initial guiding principles based on experience gained from previous ecosystem restoration projects, whose observance increases the chances of success. According to these principles, the first step is to cease or significantly reduce all human activities that damage the ecosystem in question. This typically involves prohibiting the hunting of endangered species, banning destructive fishing techniques, eliminating local sources of marine pollution, and halting the excessive extraction of resources such as sand and gravel dredging or the felling of mangrove trees for the timber trade.

If the measures taken in a restoration project are limited to this initial stage, this is referred to as passive restoration by experts. In this case, project management relies on nature to recover once all destructive interventions have ceased.

The growing population of baleen whales, for example, demonstrates that this approach can be highly effective. Since the commercial hunting of blue, fin, sei, humpback, grey and other large whales has been banned almost worldwide, their populations are recovering. However, it remains to be seen to what extent the consequences of climate change will influence this positive development.

Active restoration, on the other hand, refers to measures that go far beyond eliminating the causes of damage, involving people in the active redesign of a marine area. For example, this could involve…

- … altering the seabed or local hydrological conditions so that endangered species can once again find better living conditions. To encourage the natural colonisation of mussel beds, large quantities of empty mussel shells are scattered in coastal waters for mussel larvae to attach themselves to.

- ... removing harmful alien species to increase the chances of survival for endangered native species.

- … reintroducing native animals and plants. Prominent examples of successful restoration measures include replanting mangrove forests and seagrass beds, creating new salt marshes and approaches to the targeted reproduction and settlement of tropical corals.

In some places, project initiators are combining several approaches. In northern Norway, for instance, researchers are currently employing a two-pronged approach to halt the dramatic decline of kelp forests off the coast. On the one hand, they are introducing catfish, which have long been overfished in Norway. These catfish live on the seabed and feed on sea urchins, which are responsible for the dramatic decline in kelp forests. Where they occur in large numbers, sea urchins eat entire sections of the coastline bare.

At the same time, the researchers are placing rings covered in healthy seaweed on the seabed. These man-made 'kelp patches' are intended to attract fish and release millions of algae spores into the sea during the breeding season. This allows new, large algae to colonise the bare areas of the rocky coastline.

For the repopulation project to be successful in the long term, however, catfish, sea urchins and seaweed must exist in balanced relationships with each other. This means that catfish fishing in this coastal area must stop for the time being. This, in turn, requires the support of political decision-makers and local fishing companies for the overall project.

4. Involvement of the local population

However, politics and business are just two of the many stakeholders who must be convinced of the project's merits. The restoration of marine habitats can only succeed if all affected population groups are involved in planning and implementing the project from the outset, and if they support its objectives. In addition to scientific facts and methods from many disciplines, the knowledge of local stakeholders must also be considered.

The expertise of the local coastal population can be extremely helpful, as demonstrated by various projects to reforest damaged or destroyed mangrove forests. Thanks to the local knowledge of indigenous people, experts in Colombia were able to stop the salinisation of a dying mangrove forest, restore the regular inflow of seawater, and plant new mangroves.

Best Practice Guide to Mangrove Conservation

In their Best Practice Guide, 'Including Local Ecological Knowledge in Mangrove Restoration & Conservation', experts from the Global Mangrove Alliance and local partners present different ways in which local coastal communities can contribute their knowledge to the success of restoration projects.

5. Consideration of neighbouring ecosystems in unison

It has also proven beneficial to consider restoration plans beyond the boundaries of a single ecosystem and to take the entire coastal section into account. This is because the various ecosystems influence each other, so the loss or damage to one habitat can negatively affect neighbouring ones.

In tropical regions, for example, seagrass beds and mangroves are primarily found in areas where the movement of waves and currents is slowed by offshore coral reefs. In turn, the corals and seagrass beds benefit from the mangroves' many roots retaining sediments and ensuring sufficiently clear water, which seagrasses and corals need for photosynthesis. To strengthen the health and resilience of marine ecosystems through restoration measures, it is essential to consider how spatial conditions and the interdependencies of several habitat types can positively impact each other.

When projects are conceived, planned and implemented in such a comprehensive manner, native animals and plants also benefit – especially those species that migrate from one ecosystem to another during their lifetime. The giant mud crab Scylla serrata, for example, spends most of its life in mangroves and other coastal habitats. However, it migrates to the open sea to spawn, as its larvae cannot tolerate the low salinity of coastal waters.

Observations from a research project on newly planted seagrass beds in the German Baltic Sea illustrate how quickly marine organisms (re)colonise newly planted coastal ecosystems. Various amphipods moved into the new beds within just a few months, while the typical inhabitants of the sediment layer (soft, upper seabed layer) took around two years to do so. The important microbial community, on the other hand, was slow to return. The researchers concluded that the restoration of a seagrass bed quickly leads to an increase in local biodiversity. However, the return of species is far from complete after two years.

6. Restoration is also worthwhile for people

In light of current climate change and species extinction, successfully implementing restoration projects is more important than ever. Furthermore, the international community set itself an ambitious goal in the form of the new global agreement on biodiversity (the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework), which was agreed in 2022. By 2030, countries intend to restore 30 per cent of damaged terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

The European Union has given itself a little more time in its new law on nature restoration. It aims to restore at least 20 per cent of Europe's damaged marine areas to a healthy state by 2030, as well as all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

Successful restoration projects in various coastal areas around the world provide hope that these ambitious plans can be realised. They demonstrate that appropriate measures in the sea

- can be effective over large areas (1,000 to 100,000 hectares)

- can have an impact that lasts for decades

- can quickly have an impact beyond the project boundaries

- can be cost-effective

- can bring social and economic benefits to local people

However, in order to achieve this, they must be planned, implemented, monitored and evaluated in accordance with local conditions. All stakeholders must also change their approach to the ocean and use the restored ecosystems sustainably.

Recommended German literature:

- Löschke, S., M. Paul, S. Reents, L. Sander, M. Wölfelschneider, N. Oppelt, K. Burkhard, E. Thomsen, U. Bernitt (2025): Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse der Forschung zum CO2-Entnahmepotenzial der Seegraswiesen und Salzmarschen entlang der deutschen Küste, pp. 1-16, DOI 10.3289/CDRmare.56, https://cdrmare.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/insights_BlueCarbon_251021.pdf

Recommended English literature for interested persons:

- UNEP-WCMC (2025). Ocean+ Habitats - Explore the world's marine & coastal habitats. November 2025. habitats.oceanplus.org

- B. A. Hansen (2025). Researchers are using catfish to combat sea urchins. High North News, https://www.highnorthnews.com/nb/node/58838

- Beeston, M., Cameron, C., Hagger, V., Howard, J., Lovelock, C., Sippo, J., Tonneijk, F., van Bijsterveldt, C. and van Eijk, P. (2023): Best practice guidelines for mangrove restoration. https://www.mangrovealliance.org/best-practice-guidelines-for-mangrove-restoration

- WWF (2025): 10 Key Principles for effective marine and coastal restoration. Download unter: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/250314_wwf_publication_restoration_dina4_digital.pdf

Recommended English-language specialist literature (open access):

- Duarte, C.M., Agusti, S., Barbier, E. et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580, 39–51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2146-7

- Gann, G.D., et al. (2019): International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. Second edition. Restor Ecol, 27: S1-S46.DOI: 10.1111/rec.13035

- Lovelock, C.E., Hagger, V., Feller, I.C. et al. Mangrove biodiversity and ecosystem services. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00103-3

- Saunders, Megan I. et al. (2020): Bright Spots in Coastal Marine Ecosystem Restoration. Current Biology, Volume 30, Issue 24, R1500 - R1510, DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.10.056

- Smith, Rachel S. & Pruett, Jessica L. (2025): Oyster Restoration to Recover Ecosystem Services. Annual Review of Marine Science Volume 17, 2025, DOI: 10.1146/annurev-marine-040423-023007

- M.L. Vozzo, et al. (2023): To restore coastal marine areas, we need to work across multiple habitats simultaneously. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120 (26) e2300546120, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2300546120

- Waltham NJ, et al. (2020): UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030—What Chance for Success in Restoring Coastal Ecosystems?. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:71. DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00071